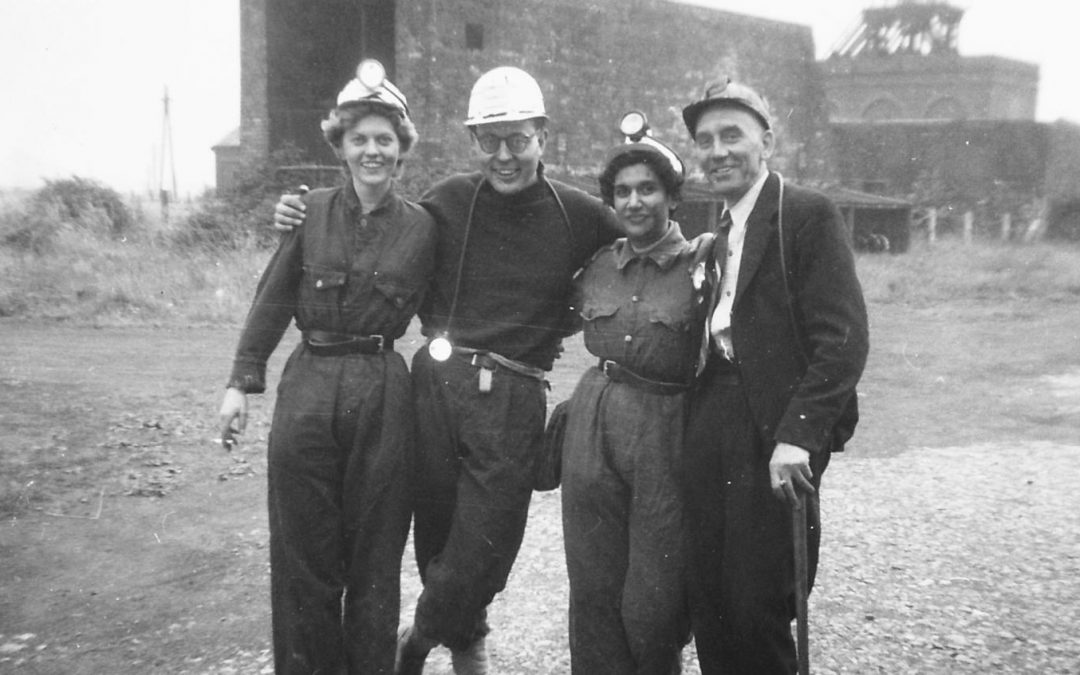

Sarah Erulkar on location with director Rodney Giesler (middle) for Watch That Trailing Cable (1957) © BFI National Archive

A hundred years after they were born, the careers of Sarah Erulkar and John Krish give us insights into a hidden history of creativity and innovation within Britain’s documentary tradition.

By Patrick Russell, BFI

Two of Britain’s most accomplished and interesting filmmakers were born 100 years ago – and chances are you’ve never heard of them. The BFI’s recent Film on Film Festival celebrated Sarah Erulkar (1923 to 2015) and John Krish (1923 to 2016) in special centenary screenings.

Both filmmakers experienced fascinating career twists and turns. Both left us captivating documentary records of life in the second half of the 20th century. And both bodies of work, while distinctly different, share several attractive features. Sensitivity, versatility and professionalism mesh with deep commitment: a commitment to filmmaking serving purposes beyond the frame of the screen, underpinned by impeccable craftsmanship within it. A remarkable control of visual composition and narrative pace is a hallmark of both directors’ work.

So if that work is so good, why are these people not famous?

Reputations

As always with cultural reputations, there are multiple factors in play, but a critical one is this: these films emerged from a sector of post-war British film – the industry making short films commissioned and paid for (in the term of the time, ‘sponsored’) by organisations ranging from corporations to public agencies and charities – that was paradoxically positioned.

Measured by scale of production, number of gifted exponents and quality of output, this was one of Britain’s most successful screen industries. Yet, simultaneously, it was virtually ignored by mainstream cultural journalism. If anything, the films garnered more prestige abroad than at home.

To add to the oddity: an earlier generation, the 1930s ‘documentary movement,’ had engaged in the same practice – sponsored filmmaking – to considerable acclaim. But after World War War II, the equivalent films fell sharply out of artistic and ideological fashion: victims, effectively, of unthinking sector – and genre – condescendence.

Among many consequences, one was that almost no-one at the time noted that it was this field, years before any other UK screen sector, that for the first time saw a non-white filmmaker (Erulkar) forge a career, in the face of obstacles, as a working film director.

Origin stories

Sarah Erulkar was born in May 1923 in Calcutta (now Kolkata), India, and John Krish in the December of that year, in London, where Erulkar was raised following her family’s relocation (generations ahead of large-scale immigration from British-colonised countries).

Both were Jewish, with Krish’s family roots lying in Russia and Poland. (In 2009, on the anniversary day of Britain’s declaration of war on Germany, Krish emailed me: “70 years ago I was 14 at home listening to Chamberlain – and suddenly afraid for all us Jews in Britain.”)

It was the 1930s documentary movement in Britain that inspired both into film, each of them later citing their youthful viewing of 1936 classic Night Mail, often screened in schools, as the trigger for their unusual career choice.

Having dropped out of high school, the 17-year-old Krish became a trainee at the government’s Crown Film Unit in 1942, having precociously turned up on spec at the Denham HQ after learning that (in their previous incarnation as the GPO Film Unit) these were the people behind Night Mail. After university, Erulkar approached both Crown and the movement’s primary private-sector offshoot, the Shell Film Unit (SFU). Shell happened to schedule her job interview just days before Crown had also scheduled one, too late to stop her accepting Shell’s immediate offer.

Ironically, it was luminaries of the 1930s movement, Arthur Elton and Edgar Anstey, who were now becoming pillars of the post-war establishment, who visited early-career crises upon both young creatives – in Erulkar’s case, straightforward sexist discrimination.

Having, as part of a then-small ethnic minority in the UK, experienced much hurtful racism in her youth, Erulkar found multinational Shell a welcoming cosmopolitan environment, and rapidly made the director’s chair, quickly coming to helm, in her early twenties, a major production, Lord Siva Danced. (There is ambiguous chronology here: Erulkar remembered this as her directorial debut, which would put it at 1946 or 1947, but it’s become canonically listed as 1948, later than other films, possibly due to getting a UK release later than its Indian one.)

This hypnotic evocation of Indian dance, and its relationship to the subcontinent’s geography and religious traditions, screens at the Film on Film Festival in the form of a 35mm print struck from the negatives in 2010 (shown then with Erulkar in attendance).

Sarah Erulkar (left) filming Lord Siva Danced (1948)© BFI National Archive

Oil isn’t mentioned in the film, Shell’s interests in newly independent India instead supplying broader PR motives for the sponsor loosely associating itself with a tasteful, respectful view of Indian culture. Erulkar had pitch-perfectly met SFU supremo Elton’s precepts (“The impact of a sponsored film upon its audience will be in inverse ratio to the number of times the sponsor insists on having his name mentioned”), and went on to further SFU successes. But on marrying a fellow (junior to her) SFU filmmaker, she found herself – in an era when women, without recourse to equal ops legislation, were typically expected to give up careers upon marriage – instantly dismissed by Elton.

The same year, Krish finally graduated from his Crown editing apprenticeship to a couple years’ freelance directing, eventually landing apparently stable employment when appointed by Elton’s close friend Anstey to his recently founded British Transport Films (BTF). BTF became the mirror to the globalised SFU: domestic, nationalised but an equally polished purveyor of classy sponsored documentary.

Krish’s fourth project there was his own first major film, The Elephant Will Never Forget (1953). This tribute to London’s closing trams became a classic, but was made without Anstey’s full authorisation, in an achingly elegiac tone that was out-of-synch with BTF’s mission to promote public transport developments positively. Anstey swiftly sacked Krish.

Criss-crossing careers

But both our heroes bounced back. To follow their careers across the 1950s and 60s is to zigzag a map of London’s bustling cottage industry in short-form filmmaking.

Not taking Shell’s knock-back lying down, Erulkar pressed ahead with a film career, with her husband’s support, and in parallel with his own. This started with freelance work at the ultra-prolific World Wide Pictures, directing the early NHS film District Nurse (1952). Meanwhile, Krish would become a World Wide employee for some years, having previously been kept going by freelance jobs on the National Coal Board’s Mining Review series.

Erulkar subsequently gained employment as an in-house editor (in other words, accepting effective demotion from direction) at the board’s newly formed internal NCB Film Unit, cutting precision-tooled training films. Production manager Ken Gay later remembered: “The cutting room was a very important stage in film-making and we were fortunate in having first-class editors [several of them women] … Sarah celebrated her partly Indian origins by wearing a sari most days.”

While there, Erulkar edited some films the NCB had outsourced to production company Basic Films, co-headed by Leon Clore, a key figure in the history of British short film. When an important project – a pro-contraceptives film for the Family Planning Association – arrived at Basic, having initially been offered to Clore associate Karel Reisz, Reisz suggested that Erulkar be hired instead. The resulting film Birthright (1958) was Erulkar’s route back into direction; she would go on to direct several times for Basic and, as far forward as the 1980s, Clore’s other company Graphic Films.

The next year, on leaving World Wide, Krish became an in-house Clore director.

Krish: the career peak

The ensuing period, from 1959 to 1964, was Krish’s career peak, packed with brilliantly humane filmmaking, which extends from lovingly crafted Graphic documentaries about school life, sponsored by the National Union of Teachers, to the film he treasured perhaps more than any other: drama-documentary Return to Life (1960), made at Basic to mark International Refugee Year.

Krish later recalled a harrowing production process, including tensions between cast members from different demographics of the former Yugoslavia. Were John alive today he’d be deeply distressed by the ever-starker contrast between contemporary media discourse about refugees and the empathy of his film (sponsored by the UK Foreign Office).

At the Film on Film Festival, this era was covered by two superb shorts: They Took Us to the Sea (1961) and I Think They Call Him John (1964). The former is a charity film for regular Clore sponsor the NSPCC, Krish having established a reputation as a sensitive director of children thanks to his school films, an earlier short feature at World Wide for the Children’s Film Foundation (CFF), and his direction of the boy in Return to Life. Transcending do-gooding, its amazingly fluent, unobtrusive control (in the face of challenging shooting conditions) of every aspect of the filmmaking process infuses its record of an urban orphaned-children’s day out in a seaside town with piercing compassion. Film on Film screened a 2010 restored print.

John Krish filming They Took Us to the Sea (1961)© BFI National Archive

The festival then screened I Think They Call Him John. This short, depicting a lonely day in the life of a housebound widower, was sponsored by the Craignish Trust and produced not by Clore but by Anne-Balfour Fraser at her firm Samaritan Films. Film on Film screened the 2010 35mm restoration. Krish’s intense, meticulous style climaxes in this towering piece of conscience-driven cinema: on the big screen, it is poignant and overwhelming.

Erulkar: the career peak

By the second half of the 1960s, Erulkar’s career was also reaching its creative peak. Unlike Krish, who began frustratedly trying to break into feature films, she consciously stuck with sponsored filmmaking – the only exceptions are her own work for the CFF (1967’s The Hunch is on BFI Player).

She too was a fine director of children, as in 1964’s The Smoking Machine, one of the earliest pieces of anti-smoking health education, delivered as a CFF-style caper. (A fascinating blog from The National Archives excavates Erulkar’s research and recommendations for the film.)

That project was executed at the Realist Film Unit, under producer J.B. Holmes, who’d been Krish’s favourite mentor at Crown, but Erulkar’s freelancing now ran the gamut of London producers, including further World Wide jobs, many for Balfour-Fraser as well as Clore, and several for Rayant Pictures and Anthony Gilkison Associates, companies consciously re-energising the sponsored short with the swing of the 60s.

Although like Krish, Erulkar was often, perhaps for gendered reasons, allocated both children’s and ‘social’ films, she shone in the burgeoning, predominantly masculine field of industrial ‘prestige’ shorts. ‘Prestige film’ was an industry term coined to categorise shorts like those Shell had pioneered: quality general interest docs, commissioned out of enlightened, relatively hands-off corporate self-interest, with soft PR rather than hard advertising motives.

Erulkar’s perfected signature style fit the bill, her mature films marked by a great eye, good taste and a feel for filmic momentum. She became particularly respected by peers for her confident, novel use of photographic and editing effects, discreetly integrating a genuine experimentalism into stylish films for middlebrow audiences.

Film on Film screened three examples. Gilkison (formerly at Rayant) had cultivated a relationship with the Gas Council, the oversight body for the then-nationalised gas industry. It was for them that Erulkar made Something Nice to Eat (1967), inviting viewers into a colourful, cosmopolitan culinary world (powered by gas cooking), far from the drear of post-war rationing. This film is super-stylish: so much so that my colleague Ros Cranston named it in her contribution to last year’s Sight and Sound Greatest Films poll. The BFI National Archive recently restored it, but the restoration has hitherto only been distributed digitally. The Film on Film festival premiered the brand new 35mm print.

Erulkar’s career zenith came in 1969, with Picture to Post. Though the GPO Film Unit was never revived, the Post Office continued commissioning films from outside suppliers (including the 1959 Krish/Clore production Counterpoint). Rayant got the contract for a film about contemporary stamp design. The GPO specified that an “atmosphere of control, care and beauty must be created” by the film; Rayant, having contracted Erulkar for an earlier GPO short, replied: “The more we talk about the techniques to be employed, the more it becomes a ‘natural’ for Sarah Erulkar to direct.” (These quotes come from the production file preserved by our friends at the Postal Museum. Ros will be digging more deeply into the production’s history in a special talk following the centenary screening).

Sarah Erulkar in production on Picture to Post (1969)© BFI National Archive

It’s a case of form and content being coterminous, both centring on immaculate design. Particularly notable for successful experiments with split-screen, Picture to Post received a BAFTA and – so GPO claimed – the most extensive theatrical distribution, national and international, of any sponsored short film since the war.

As Erulkar’s prime coincided with a period in which more standalone shorts were getting theatrically released than for a generation, and with Gilkison’s enthusiasm for pursuing those opportunities, I’d speculate (though can’t prove) that she has her name on more cinema-released shorts than any other British director.

Finishing lines

The final Erulkar film screening in Film on Film is The Air My Enemy: an original release print still in great nick. A repeat commission from Gilkison and the Gas Council, it was a very different animal than its predecessor. As the booming 60s shaded into the gloomy 70s, the sponsored film was drawn to the emergent subject of environmental degradation. An entire cycle of ecologically-themed industrial films hit early-70s screens (the most famous being BP film The Shadow of Progress (1970), directed by Derek Williams). It’s a moot point whether this was a case of film laudably visualising growing concerns, or of early greenwashing by guilty corporates, or of filmmakers navigating the pitfalls between the two. I’d argue all three, but it’s anyway fascinating to compare the multiple examples.

Erulkar’s again stands out for sheer style, superimpositions bringing an almost ghostly quality to its environmental warnings (coupled, of course, with the sponsor’s enthusiasm for natural gas as a supposedly clean energy source).

Another theatrically released film, Erulkar and Gilkson’s Design in Steel (1973) is available on BFI Player. Being comprised of designer case-studies, it’s effectively a lower-budget replay of Picture to Post, for a different client (British Steel). But it’s essential Erulkar, kitschy music never distracting from meticulously orchestrated visuals.

The sector was changing, however. Across the decade, economic crises caused big industry to reduce investment in glossy films, with lower-key educational and public information projects increasingly more reliable sources of work. For instance, again for children, Erulkar and Balfour-Fraser made one of the era’s best-remembered (and scariest) public information films (PIFs), Never Go with Strangers (1971).

On re-entering the sector following his abortive features period, Krish became indelibly associated in the trade with what is now nostalgically considered the golden age of the PIF. Increasingly contracting with advertising production companies, he alternated product commercials (such as this Guinness spot) with masterful PIFs that were similarly transmitted in TV ad breaks. From the heart-stopping The Sewing Machine (1973) to the soul-hurting Searching (1974).

Much longer, and made for 16mm screenings, the final two terrific Krish shorts screening in Film on Film are studies in how stylistically different public safety films can be, the differences here deriving precisely from the filmmaker’s obsession with understanding and reaching his varied target audiences.

I Stopped, I Looked and I Listened (1975) – road safety advice aimed at elderly people – is an apparently modest film of great gentleness that gradually becomes ineffably moving: another thoughtful piece about old age itself. By contrast, The Finishing Line (1977), aimed at school kids, is surreal and savage. Anstey’s successor John Shepherd had invited Krish back to BTF to make this graphic warning against playing on railway tracks. Along with Never Go with Strangers and other ‘danger’ films of that era like Lonely Water (1973) and Apaches (1977), it’s become a cult favourite online among its original target demographic, now in late middle age. But in analogue form on a big screen (it screened at Film on Film via one of the original 16mm prints that circulated through schools in 1977), it’s genuinely terrifying.

The terror was calculated, and carefully calibrated, as a form, almost, of shock aversion therapy – which in my view was a product of Krish’s committed humanism rather than anything exploitative. But some parents objected, journalists picked up on it and controversy briefly flared.

Today we’re familiar with the argument that if a piece of awareness-raising content becomes a divisive talking-point in mainstream media, that’s a great way to draw attention to its message. But that was not Krish or Shepherd’s intention, they’d aimed the film squarely at a tightly defined age demographic of pre-adolescents and they wanted them to see it. I’ve heard that Anstey, after Shepherd withdrew the film under public pressure, and having previously warned him against hiring Krish, now wrote him an ‘I told you so!’ memo.

Ironically, it was Anstey who’d not long before presented Krish with the Grierson Award for another out-there (road) safety film, Drive Carefully, Darling (1975). They were all smiles on that occasion, onstage at least.

John Krish receiving a Grierson Award from Edgar Anstey for his 1975 film Drive Carefully, Darling© BFI National Archive

Counterparts and counterpoints

Erulkar and Krish had both retired by the late 1980s. It wasn’t until this century that they began to get interviewed and written about. Some interesting comparisons bring us right back to the issues of reputation-building.

For one, consider another future filmmaker born in British-ruled India in 1923: two weeks before Erulkar and almost 1,000 miles away, in Bangalore. That 1923 baby, Lindsay Anderson, would become far better-known than her or Krish on account of a handful of feature films (including 1968’s If….) that had major cultural impact, his leadership of the earlier ‘Free Cinema’ movement in short film, his pioneering and voluminous film criticism, influential theatre direction, and no little self-promotion.

But the least-known part of Anderson’s career was spent in close professional proximity to our, perhaps more self-effacing, heroes.

Anderson’s first attempts at semi-professional filmmaking were in regional industrial films, following which he entered Clore’s orbit, like Krish making films at Basic for such regular sponsors as the COI and NSPCC (a 16mm print of Anderson’s 1955 NSPCC short, Henry, in which he makes a cameo appearance, also incidentally screens during the festival’s recreation of a night at a local film society). Then two of the key Free Cinema films were made by Anderson and Reisz at Graphic, with Clore producing. Free Cinema was briefly sensational, but an often-forgotten aspect of its impact was on the ‘un-free’, and unsung, sponsored documentary industry, against which Anderson railed.

Krish later remembered ensuing arguments at Clore’s offices: “I never wanted even a sprocket-hole [of Free Cinema] … Lindsay and I argued about it, Karel and I argued about it, and I think they thought I was conventional.”

The disagreements centred on two major matters. Firstly a question of style, Krish advocating for controlled, purposeful directing: “I loathe improvisation … [Free Cinema] seemed to me the most amateur way of going about things.” Secondly matters of motivation: “Free Cinema was masturbation, frankly … They just seem to be making films for themselves, and I find that contemptible.”

Agree or not, there does seem a fundamental difference between how filmmakers like Anderson and Reisz conceived of and marketed themselves, and how those like Krish and Erulkar did, with a knock-on effect on cultural visibility. Krish and Erulkar clearly considered themselves professional communicators, with a duty to their funders and audiences, rather than, primarily, as self-expressive auteurs. But be in no doubt: that by no means excluded their burning personal passion for their projects and their medium. Quite the opposite, in fact: in Krish’s case it brought him into frequent, brave conflict with his own clients.

Lindsay Anderson filming for Leon Clore’s Graphic Films© BFI National Archive

Interestingly, during Anderson’s theatre period, it was TV commercials that kept one foot in the movie-making business, these Anderson ads being made at Clore’s company Film Contracts, which doled out advertising work to many of his associates – including Krish.

Erulkar later drily observed that Free Cinema might only have been possible due to the amount of advertising work its exponents took on, citing Krish in that context too. Krish, indeed, was always open about the fact that it was his advertising jobs that made it even possible to take on the unprofitable labour-of-love projects yielding much of his best filmmaking. (It’s unclear why Erulkar was never on Film Contracts’ books: perhaps because she’d only ever freelanced for Clore rather than been full-time employed by him.)

All three filmmakers acknowledged Clore – and in Erulkar and Krish’s cases, Balfour-Fraser – as great producers, ever-protective of creatives’ visions, even as those visions diverged from each other. (Clore and Balfour-Fraser were independently wealthy, arguably a factor in their greater willingness to challenge their sponsors than self-made producers more worried about paying the bills.)

The other comparison we might draw is with filmmaking today. It’s still the case that feature films, and nowadays higher-end TV, dominate cultural criticism. And it’s still the case that there are so many other screen industries out there – hidden screen industries, flourishing, often on gigantic scale, under the critical radar.

Some of these are close contemporary parallels to the sector in which Erulkar and Krish made their mini-masterpieces so many decades ago. Many of Erulkar’s finest films from Lord Siva Danced to Design in Steel were – in effect, though generations before the term was coined – ‘branded content’, a screen practice now booming online. And social awareness-raising films like those that Krish, and sometimes Erulkar, so brilliantly directed for charities and other NGOs are similarly central to the online video era.

To rediscover the great work made on 35mm and 16mm film by the likes of Krish and Erulkar is a rewarding pleasure in itself. But it’s also a lesson for us to do better at understanding the scope, power and variety of moving image making in our own digital era. How many fine practitioners, quietly crafting fine, purposeful, short-form filmmaking in busy but unglamorous contemporary screen sectors, will have to wait until their own old age to gain due recognition?

First published on the BFI website here: Giants in the shadows: celebrating the centenaries of Sarah Erulkar and John Krish | BFI